Guest Post: The Song of the Merchant Ship

A folksong from Kerala, contributed by Subramanian Subramanian

It was a hot April morning. A flock of sparrows flew hopefully onto the quayside in search of food. A large white-and-grey gull with a coffee-brown head was perched upon the handrail of a large cargo ship and observing the sparrows with a friendly but patronising air. “Oi, you lot!” he screeched. “Come on up! There’s loads to eat on board!”

The sparrows did not need a second invitation and, with a whirring of wings, flew as one onto the ship. The ship was loading sacks of grain which the stevedores had piled upon the deck. The hospitable gull helpfully pecked a hole in one of the sacks with its sharp beak. The grain came spilling out and the sparrows began greedily stuffing themselves. So engrossed were they in filling their tummies they did not notice the ship moving away from the dock even though it sounded its horn loudly several times.

The seagull, meanwhile, was enjoying the sea breeze and humming happily and tunelessly to himself. “It’s been twenty-one days since the ship set sail…” sang the seagull loudly.

“What do you mean? The ship set sail?” cried the sparrows looking wildly around. The ship had moved quite far out into the sea and all they could see was water. “What do we do? What do we do?” they fluttered in panic.

“Relax, mates, the ship will hit the first port soon, and you can fly back home from there quite easily,” said the seagull. “Meanwhile, listen to this song I heard, it’ll cheer you up and pass the time!”

And this is the song the seagull sang.

THE SONG OF THE MERCHANT SHIP

A folksong from Kerala, contributed by Subramanian Subramanian

The profitably-operating merchant ship

Dropped anchor on reaching Kochi.

Paper, glass, biscuits, chimney-lamps,

Umbrellas, lace, sugar, varieties of cloth,

Knives, bells, porcelain, machinery, whisky,

Matchboxes, kerosene, muslin—

Many such items were unloaded on shore.

Then local cargo was successfully loaded—

Copra, coir, oil, pepper, ginger,

Rubber, leaf tea, herbal oil, cardamom,

Tapioca, timber, coffee, and oranges.

The ship, filled with all these items,

Sailed forth to the port of Bombay

Where, onto an enormous “fire” ship, the cargo was loaded.

This beautiful vessel that the waves couldn’t shake,

Westwards sped to a rhythmic beat—

Across the Arabian Sea, from Bab-el-Mandeb

To the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal,

Sighting Port Said, into the Mediterranean,

And past the isles of Malta.

Sailing slowly, the ship passed Gibraltar,

And entered the Atlantic Ocean.

After the stormy winds of Biscay,

The English Channel at last lay before it.

Crossing Dover, the ship entered the Thames—

It’s been a full twenty-one days since the ship set sail.

Queen Mary and King George,

And gathered Londoners, cheer!

As the seagull finished his song, the first port came into view. “Look, look, land ahoy!” called the sparrows excitedly, and off they flew, relieved to be back on land.

“Goodbye,” screeched the gull after them and wheeled up into the sky to join the other gulls diving and flying over the harbour.

The Song of the Merchant Ship has been generously contributed to The Story Birds by a close friend, Subramanian Subramanian. This folksong from Kerala was an intrinsic part of his childhood. In Subbu’s words: “Some of my most tender memories of childhood are of my maternal grandmother—her gnarled fingers combing my hair as I lay with my head on her lap, listening to her singing or telling me stories in Tamizhalam and Malayalam. It is from her that I learnt this ‘mercantile’ song, which now remained only as bits and pieces in my memory. I knew that my mother’s older sister, my Periamma, knew this song, and upon my request she sang it for me — with great gusto at the ripe old age of 93!”

The original song, in Malayalam, as sung by Subbu’s Periamma may be heard here on longlongtimeago.com:

Mechamodu paayunna kachavada kappal: a ‘mercantile’ song from Kerala

The recording is accompanied by Subbu’s transcription of the original Malayalam into Roman script, and his detailed line-by-line translation of the song into English.

Song translation credit and copyright © Subramanian Subramanian 2021

The Story Birds would like to thank Ashok Raj, writer and illustrator, for his invaluable editorial help and advice.

Brown-headed gulls are migratory birds found from September to April along the eastern and western coasts of India. They frequent harbours and fishing villages, and can be seen gliding and circling around ships and fishing boats in search of scraps. Over the summer, they breed in colonies in Ladakh and Tibet, in the bogs and marshes around Mansarovar and other lakes. They may be seen in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar as well. Their numbers, however, are declining at an alarming rate.

EDITORS’ NOTE

The Song of the Merchant Ship describes the trade between Kochi and London during the reign of George V (1910-1936) and his consort, Mary. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 significantly shortened the sea route to and from India and the invention of steam-powered ships — the enormous “fire” ship in our song — facilitated the rapid movement of goods and people across the world.

The history of trade between India and Britain — first, from 1612 through the East India Company and then, from 1857, as directed by the Crown — and the use of trade by the colonial British government for the complete political and economic subjugation of India and the ruthless exploitation of its economy, is a well-known story and needs no exposition here. For industrial Britain, India was a source of cheap raw materials and a captive market for expensive manufactured goods. In the 17th century, India was the world’s largest exporter of textiles to the world, including Britain. By the 19th century, through a combination of protective tariffs, legislature banning the import of Indian textiles into Britain, and technological innovation that increased productivity and lowered cost of production in British textile mills, Britain had taken the place of world leader in textile production. India now became a net importer of textiles and Britain’s largest market. By the 1920s, India was importing expensive, high-value added goods from Britain such as sugar, iron and steel, machinery, metal manufactures, and cotton textiles, and exporting low-value agricultural goods such as raw cotton, tea, and spices. This trade imbalance is quite accurately reflected in our song.

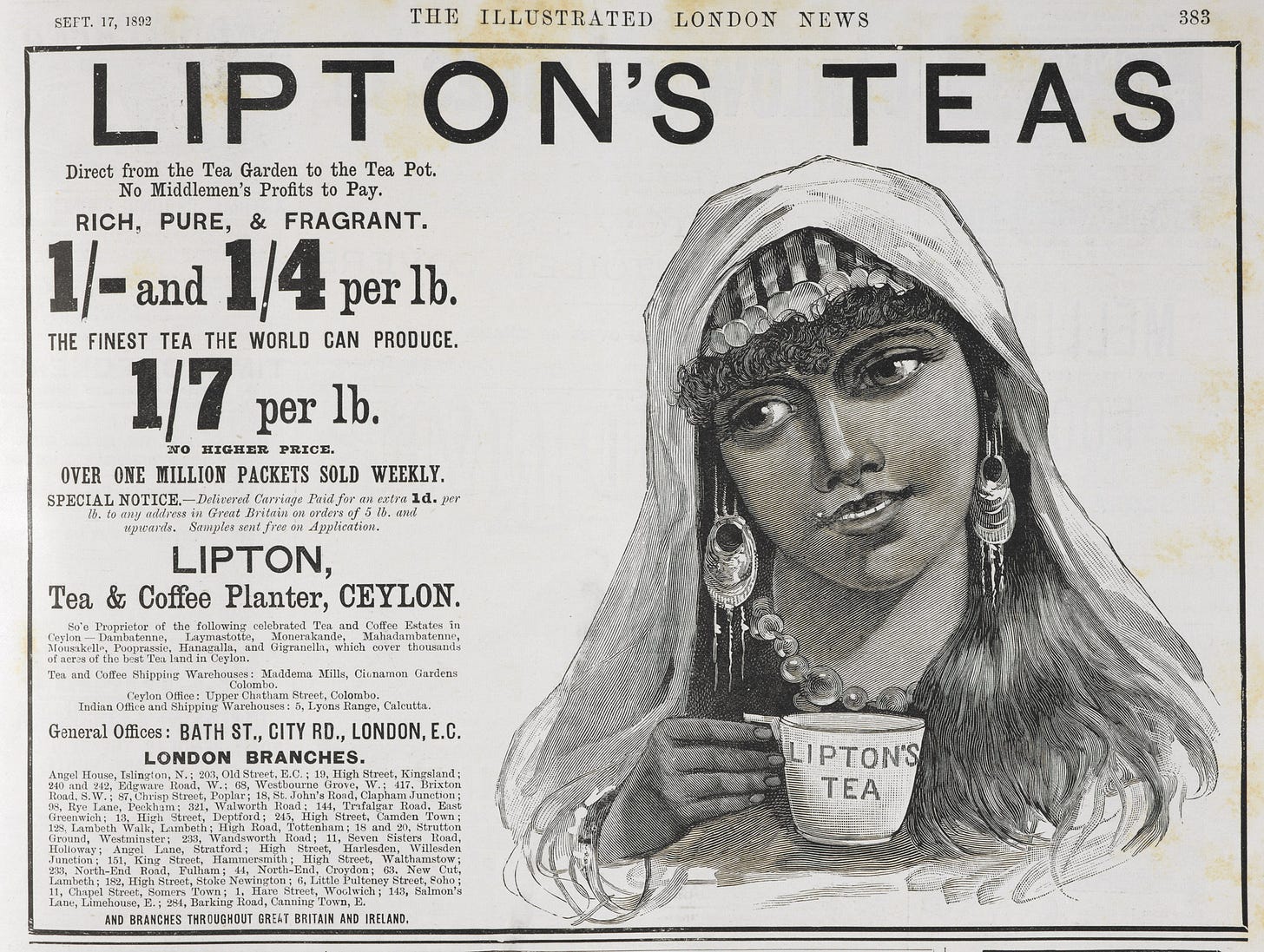

Here is an advertisement for Lipton’s Teas, published on September 17th in The Illustrated London News. Lipton’s is a brand still popular in India!

We were particularly intrigued by the bells in the list of items brought by the merchant-ship to Kochi. What kind of bells might these be? Despite hours of reading through trade records, we could not find any mention of bells anywhere. Subbu had the best explanation — that the bells in the song probably refer to the huge bell-metal bells manufactured in Britain and intended for churches in India. Temple bells, as Subbu pointed out, were made in India, but this was not always the case with church bells. This sounds plausible, given the large volume of metal manufactures exported to India by Britain.

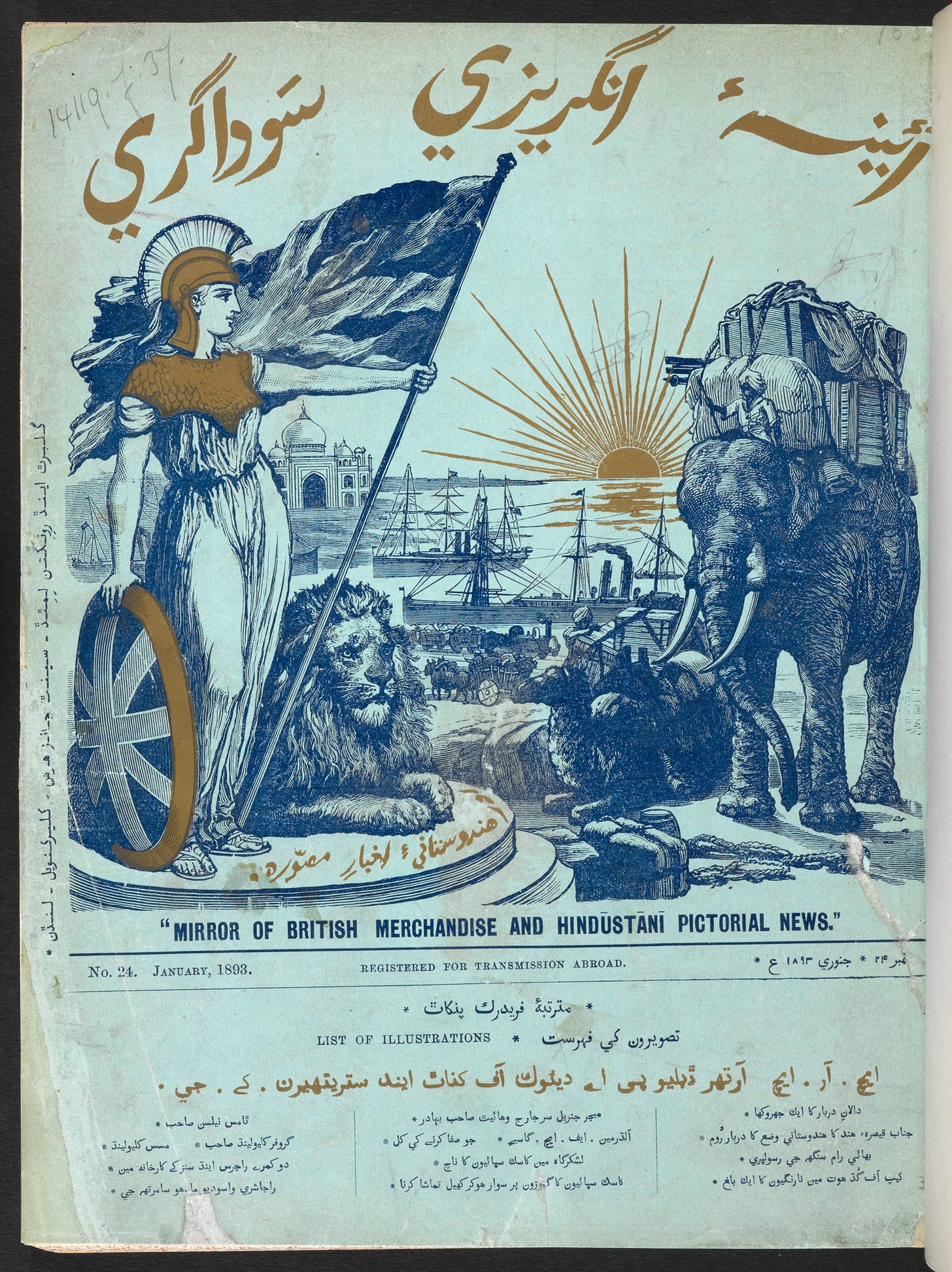

Here is the cover of a January 1893 issue of the weekly Aaina-e-Angrezi Saudagari, (translated on the cover as ‘The Mirror of English Merchandise’) a propaganda magazine published in India extolling the virtues of British rule and promoting the sale of expensive, British-manufactured consumer goods to Indian buyers.

In the background, goods are being loaded on to steamships setting sail for Britain.

Songs such as the one we have presented here often served as mnemonic devices — in this case, perhaps to remember the items the ship brought in and took away, or to remember the route the steamship took, from Kochi to Bombay and thence to London.

We attempted to map the ship’s journey on Google Maps. Here it is, the result of our efforts:

We’re very excited to have discovered this wonderful song. Do you know of any other, similar ones? Please do write in and let us know or leave a comment below:

Sources and Further Reading

Global Trade and Empire, by Susheila Nasta, Florian Stadtler, Rozina Visram. British Library: South Asians in Britain.

See also the related list of collection items on the page.For an analysis of the cotton textiles trade between India and Britain and the shifting of comparative advantage from India to Britain, see: Cotton Textiles And The Great Divergence: Lancashire, India And Shifting Competitive Advantage, 1600-1850, by Stephen Broadberry and Bishnupriya Gupta.

For a summary of Indian textiles and their role both in the subjugation of India by Britain and then as a symbol of freedom in the fight for Indian independence, see: The Fabric of India: Textiles in a Changing World from the V&A.

For a summary of trade relations between India and Britain from 1800 to 1947, see: Trade Policy, 1800–1947.

For more on trade between India and Britain:

Appleyard, Dennis R. “The Terms of Trade between the United Kingdom and British India, 1858–1947.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 54, no. 3 (2006): 635–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/500031

And for your viewing pleasure, this week from The Story Bird ARCHIVE:

Deliverance: A film by Zachary Coffin

This is a very interesting post with lots of history I did not know. I think my favorite part, though, is the sparrows who freak out when they realize the ship has sailed and they are on it. I'm pretty sure Ive had the same reaction at different times in my life. A common human ailment: when life gives us what we want, we become afraid and choose to return to safe land instead of enjoying the bountiful journey.