Hudden and Dudden and Donald O'Neary

A Celtic folktale, as collected and retold by Joseph Jacobs

A fat red hen was scratching for grain in the farmyard. A bunch of hungry sparrows, perched upon the fence, watched longingly.

“Come on, join me, there is plenty here for us all,” clucked the red hen.

The sparrows didn’t need to be asked twice. They fluttered down to join her and began pecking away at the grain as fast as they could.

“My, you must be starving,” remarked the hen, and nudged some more grain towards them.

“Thank you, ma’am,” mumbled the sparrows through full beaks, suddenly remembering their manners.

“I don’t see so many of you these days,” said the red hen. “Is food scarce out there?”

“The woods and fields are disappearing,” explained a sparrow. “The ground is hard and black and nothing grows on it. It’s only good for cars and people.”

“That sounds frightening,” said the red hen, looking horrified.

“It is,” nodded the sparrow. “We are really grateful for the grain today.”

“We are neighbours after all,” said the hen. “It does the world no good when neighbours don’t get along.” And she plumped up her feathers and settled down comfortably, ready with a story.

The sparrows gathered around eagerly.

And this is the tale the red hen told.

Hudden and Dudden and Donald O'Neary

As collected and retold by Joseph Jacobs

There was once upon a time two farmers, and their names were Hudden and Dudden. They had poultry in their yards, sheep on the uplands, and scores of cattle in the meadow-land alongside the river. But for all that they weren't happy. For just between their two farms there lived a poor man by the name of Donald O'Neary. He had a hovel over his head and a strip of grass that was barely enough to keep his one cow, Daisy, from starving, and, though she did her best, it was but seldom that Donald got a drink of milk or a roll of butter from Daisy. You would think there was little here to make Hudden and Dudden jealous, but so it is, the more one has the more one wants, and Donald's neighbours lay awake of nights scheming how they might get hold of his little strip of grass-land. Daisy, poor thing, they never thought of; she was just a bag of bones.

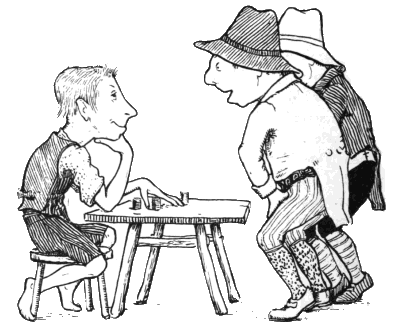

One day Hudden met Dudden, and they were soon grumbling as usual, and all to the tune of "If only we could get that vagabond Donald O'Neary out of the country."

"Let's kill Daisy," said Hudden at last; "if that doesn't make him clear out, nothing will."

No sooner said than agreed, and it wasn't dark before Hudden and Dudden crept up to the little shed where lay poor Daisy trying her best to chew the cud, though she hadn't had as much grass in the day as would cover your hand. And when Donald came to see if Daisy was all snug for the night, the poor beast had only time to lick his hand once before she died.

Well, Donald was a shrewd fellow, and downhearted though he was, began to think if he could get any good out of Daisy's death. He thought and he thought, and the next day you could have seen him trudging off early to the fair, Daisy's hide over his shoulder, every penny he had jingling in his pockets. Just before he got to the fair, he made several slits in the hide, put a penny in each slit, walked into the best inn of the town as bold as if it belonged to him, and, hanging the hide up to a nail in the wall, sat down.

"Some of your best whisky," says he to the landlord. But the landlord didn't like his looks. "Is it fearing I won't pay you, you are?" says Donald; "why I have a hide here that gives me all the money I want." And with that he hit it a whack with his stick and out hopped a penny. The landlord opened his eyes, as you may fancy.

"What'll you take for that hide?"

"It's not for sale, my good man."

"Will you take a gold piece?"

"It's not for sale, I tell you. Hasn't it kept me and mine for years?" and with that Donald hit the hide another whack and out jumped a second penny.

Well, the long and the short of it was that Donald let the hide go, and, that very evening, who but he should walk up to Hudden's door?

"Good-evening, Hudden. Will you lend me your best pair of scales?"

Hudden stared and Hudden scratched his head, but he lent the scales.

When Donald was safe at home, he pulled out his pocketful of bright gold and began to weigh each piece in the scales. But Hudden had put a lump of butter at the bottom, and so the last piece of gold stuck fast to the scales when he took them back to Hudden.

If Hudden had stared before, he stared ten times more now, and no sooner was Donald's back turned, than he was off as hard as he could pelt to Dudden's.

"Good-evening, Dudden. That vagabond, bad luck to him—"

"You mean Donald O'Neary?"

"And who else should I mean? He's back here weighing out sackfuls of gold."

"How do you know that?"

"Here are my scales that he borrowed, and here's a gold piece still sticking to them."

Off they went together, and they came to Donald's door. Donald had finished making the last pile of ten gold pieces. And he couldn't finish because a piece had stuck to the scales.

In they walked without an "If you please" or "By your leave."

"Well, I never!" that was all they could say.

"Good-evening, Hudden; good-evening, Dudden. Ah! you thought you had played me a fine trick, but you never did me a better turn in all your lives. When I found poor Daisy dead, I thought to myself, 'Well, her hide may fetch something;' and it did. Hides are worth their weight in gold in the market just now."

Hudden nudged Dudden, and Dudden winked at Hudden.

"Good-evening, Donald O'Neary."

"Good-evening, kind friends."

The next day there wasn't a cow or a calf that belonged to Hudden or Dudden but her hide was going to the fair in Hudden's biggest cart drawn by Dudden's strongest pair of horses.

When they came to the fair, each one took a hide over his arm, and there they were walking through the fair, bawling out at the top of their voices: "Hides to sell! hides to sell!"

Out came the tanner. "How much for your hides, my good men?"

"Their weight in gold."

"It's early in the day to come out of the tavern." That was all the tanner said, and back he went to his yard.

"Hides to sell! Fine fresh hides to sell!"

Out came the cobbler. "How much for your hides, my men?"

"Their weight in gold."

"Is it making game of me you are! Take that for your pains," and the cobbler dealt Hudden a blow that made him stagger.

Up the people came running from one end of the fair to the other. "What's the matter? What's the matter?" cried they.

"Here are a couple of vagabonds selling hides at their weight in gold," said the cobbler.

"Hold 'em fast; hold 'em fast!" bawled the innkeeper, who was the last to come up, he was so fat. "I'll wager it's one of the rogues who tricked me out of thirty gold pieces yesterday for a wretched hide."

It was more kicks than halfpence that Hudden and Dudden got before they were well on their way home again, and they didn't run the slower because all the dogs of the town were at their heels.

Well, as you may fancy, if they loved Donald little before, they loved him less now.

"What's the matter, friends?" said he, as he saw them tearing along, their hats knocked in, and their coats torn off, and their faces black and blue. "Is it fighting you've been? or mayhap you met the police, ill luck to them?"

"We'll police you, you vagabond. It's mighty smart you thought yourself, deluding us with your lying tales."

"Who deluded you? Didn't you see the gold with your own two eyes?"

But it was no use talking. Pay for it he must, and should. There was a meal-sack handy, and into it Hudden and Dudden popped Donald O'Neary, tied him up tight, ran a pole through the knot, and off they started for the Brown Lake of the Bog, each with a pole-end on his shoulder, and Donald O'Neary between.

But the Brown Lake was far, the road was dusty, Hudden and Dudden were sore and weary, and parched with thirst. There was an inn by the roadside.

"Let's go in," said Hudden; "I'm dead beat. It's heavy he is for the little he had to eat."

If Hudden was willing, so was Dudden. As for Donald, you may be sure his leave wasn't asked, but he was lumped down at the inn door for all the world as if he had been a sack of potatoes.

"Sit still, you vagabond," said Dudden; "if we don't mind waiting, you needn't."

Donald held his peace, but after a while he heard the glasses clink, and Hudden singing away at the top of his voice.

"I won't have her, I tell you; I won't have her!" said Donald. But nobody heeded what he said.

"I won't have her, I tell you; I won't have her!" said Donald, and this time he said it louder; but nobody heeded what he said.

"I won't have her, I tell you; I won't have her!" said Donald; and this time he said it as loud as he could.

"And who won't you have, may I be so bold as to ask?" said a farmer, who had just come up with a drove of cattle, and was turning in for a glass.

"It's the king's daughter. They are bothering the life out of me to marry her."

"You're the lucky fellow. I'd give something to be in your shoes."

"Do you see that now! Wouldn't it be a fine thing for a farmer to be marrying a princess, all dressed in gold and jewels?"

"Jewels, do you say? Ah, now, couldn't you take me with you?"

"Well, you're an honest fellow, and as I don't care for the king's daughter, though she's as beautiful as the day, and is covered with jewels from top to toe, you shall have her. Just undo the cord, and let me out; they tied me up tight, as they knew I'd run away from her."

Out crawled Donald; in crept the farmer.

"Now lie still, and don't mind the shaking; it's only rumbling over the palace steps you'll be. And maybe they'll abuse you for a vagabond, who won't have the king's daughter; but you needn't mind that. Ah! it's a deal I'm giving up for you, sure as it is that I don't care for the princess."

"Take my cattle in exchange," said the farmer; and you may guess it wasn't long before Donald was at their tails driving them homewards.

Out came Hudden and Dudden, and the one took one end of the pole, and the other the other.

"I'm thinking he's heavier," said Hudden.

"Ah, never mind," said Dudden; "it's only a step now to the Brown Lake."

"I'll have her now! I'll have her now!" bawled the farmer, from inside the sack.

"By my faith, and you shall though," said Hudden, and he laid his stick across the sack.

"I'll have her! I'll have her!" bawled the farmer, louder than ever.

"Well, here you are," said Dudden, for they were now come to the Brown Lake, and, unslinging the sack, they pitched it plump into the lake.

"You'll not be playing your tricks on us any longer," said Hudden.

"True for you," said Dudden. "Ah, Donald, my boy, it was an ill day when you borrowed my scales."

Off they went, with a light step and an easy heart, but when they were near home, who should they see but Donald O'Neary, and all around him the cows were grazing, and the calves were kicking up their heels and butting their heads together.

"Is it you, Donald?" said Dudden. "Faith, you've been quicker than we have."

"True for you, Dudden, and let me thank you kindly; the turn was good, if the will was ill. You'll have heard, like me, that the Brown Lake leads to the Land of Promise. I always put it down as lies, but it is just as true as my word. Look at the cattle."

Hudden stared, and Dudden gaped; but they couldn't get over the cattle; fine fat cattle they were too.

"It's only the worst I could bring up with me," said Donald O'Neary; "the others were so fat, there was no driving them. Faith, too, it's little wonder they didn't care to leave, with grass as far as you could see, and as sweet and juicy as fresh butter."

"Ah, now, Donald, we haven't always been friends," said Dudden, "but, as I was just saying, you were ever a decent lad, and you'll show us the way, won't you?"

"I don't see that I'm called upon to do that; there is a power more cattle down there. Why shouldn't I have them all to myself?"

"Faith, they may well say, the richer you get, the harder the heart. You always were a neighbourly lad, Donald. You wouldn't wish to keep the luck all to yourself?

"True for you, Hudden, though 'tis a bad example you set me. But I'll not be thinking of old times. There is plenty for all there, so come along with me."

Off they trudged, with a light heart and an eager step. When they came to the Brown Lake, the sky was full of little white clouds, and, if the sky was full, the lake was as full.

"Ah! now, look, there they are," cried Donald, as he pointed to the clouds in the lake.

"Where? where?" cried Hudden, and "Don't be greedy!" cried Dudden, as he jumped his hardest to be up first with the fat cattle. But if he jumped first, Hudden wasn't long behind.

They never came back. Maybe they got too fat, like the cattle. As for Donald O'Neary, he had cattle and sheep all his days to his heart's content.

“Served those two meanies right,” said the sparrows, and returned to their feast.

This folk tale was collected in Joseph Jacobs' Celtic Fairy Tales and was illustrated by John D. Batten. The collection was published in 1892. It is in the public domain worldwide because the author died more than 100 years ago.

This text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply.

All the chickens we see on our farms today are descended from the red junglefowl (‘jangli murghi’ in Hindi). This brightly coloured bird is indigenous to India. It is found all across northern India, from the Himalayan foothills to eastern Assam and south to the Godavari river in Madhya Pradesh, and in Burma. According to the celebrated ornithologist, Salim Ali, its distribution coincides almost exactly with that of the sal tree and the swamp deer.

EDITORS’ NOTE

A poor but clever man outwitting his rich and greedy neighbour, brother, or master is a common trope in folklore. Such a story is often funny or slapstick, though a darker mood may be sensed beneath the surface humour. The cruelty of the rich towards the less fortunate is described matter-of-factly, and their comeuppance with great relish and satisfaction.

In his notes to the story of ‘Hudden and Dudden and Donald O’Neary’, Joseph Jacobs gives examples of similar tales found across the world. The eleventh century Latin poem, Unibos, describes how a poor peasant outsmarts the secular and ecclesiastical authorities of his village with his sly cunning. This poem, says Jacobs, already had the main outlines of our story, including the fraudulent sale of worthless objects and the escape from the sack trick. A similar story, says Jacob, also occurs in Giovanni Francesco ‘Gianfrancesco’ Straparola’s collection of folk and fairy tales The Facetious Nights (published sometime during the first half of the 16th century, this is the earliest collection of folk and fairy tales in Europe). The gold sticking to the scales is found in the story of Ali Baba and as well as in several folktales from India and the Slavic countries. Jacobs points out that the motif of the “cunning fellow tied in a sack getting out by crying ‘I won't marry the princess’,” is also found in stories from countries as far apart as Ireland, Sicily, Afghanistan, and Jamaica. This, he says is too much of a coincidence to accept that the tales are unconnected to each other, and it is highly likely that some borrowing must have occurred. But, as Jacobs points out, it is difficult to say who borrowed from whom or where the story might first have occurred. Jacobs concludes that the story of Hudden and Sudden “is a type of Celtic folk-tales which are European in spread, have analogies with the East, and can only be said to be Celtic by adoption and by colouring”. Despite this, Jacobs believes that such stories form a distinct section of the tales told by the Celts and must be included in any discussion of their folklore.

Do you know any similar tales? We’d love to hear them! Write in to us via the comment box below.

About Joseph Jacobs

Joseph Jacobs (1854-1916) was a scholar of Jewish history and culture and one of the leading folklorists of our modern age. Though a prolific writer and literary critic, he is best remembered for his works on folklore and fairy tales. From 1890 to 1916 he edited several collections of fairy tales, the most famous of which is perhaps English Fairy Tales (1890), followed by More English Fairy Tales (1893). These collections included such perennials as ‘Jack the Giant Killer’, ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’, and ‘The Story of the Three Bears’ (a version of which became famous as ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’).

Other collections of folklore that he edited include Celtic Fairy Tales (published in 1892 and from which is taken our story this week), Indian Fairy Tales (1892), The Fables of Aesop (1894), The Book of Wonder Voyages (1896), and European Folk and Fairy Tales (1916). He was inspired in his endeavours by the work of the Brothers Grimm. From 1899-1900, he also edited the British journal, Folklore.

In 1900 he migrated with his family to the United States of America. During his lifetime, Jacobs came to be regarded as a leading authority on folklore. He also received widespread acclaim for his study of Jewish history and culture. He died on January 30, 1916, in New York.

FURTHER READING

For more about Joseph Jacobs and stories from his collection of English fairy tales, see longlongtimeago.com: Joseph Jacobs

For his complete collection of Celtic tales, see Celtic Fairy Tales, by Joseph Jacob\

Did you like our story? Tell us what you think!

From The Story Bird ARCHIVE:

Twenty-Four Bends in the Min River: the story of Wen P’eng and the Magic Pearl

Thank you for reading The Story Birds. To support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Your support keeps the stories flowing.